Every time somebody asks how I spent the COVID-19 lockdown, I get flashbacks to hosting virtual listening sessions for students about their school closures or transitioning a team-bonding game of “Among Us” into a last minute processing space for the January 6 insurrection. As a peak pandemic college student, I didn’t bake banana bread, attempt a sourdough starter, make whipped coffee or record a single TikTok dance. Instead, I spent 60 hours a week on Zoom in my childhood bedroom operating a national youth-led education justice organization, Student Voice, that officially sunset this fall.

Alongside a Zoom fatigue I’m not sure will ever entirely go away is a whole host of literal baggage: I’ve carted cases of leftover school board campaign stickers to three post-grad apartments. There’s a dinosaur-aged Dell laptop with the organization’s original QuickBooks accounting spreadsheets collecting dust in my parents’ house. My dad has gone through an entire case of branded ballpoint pens in the time it's taken me to discern even my initial reflections from my college years as a nonprofit director.

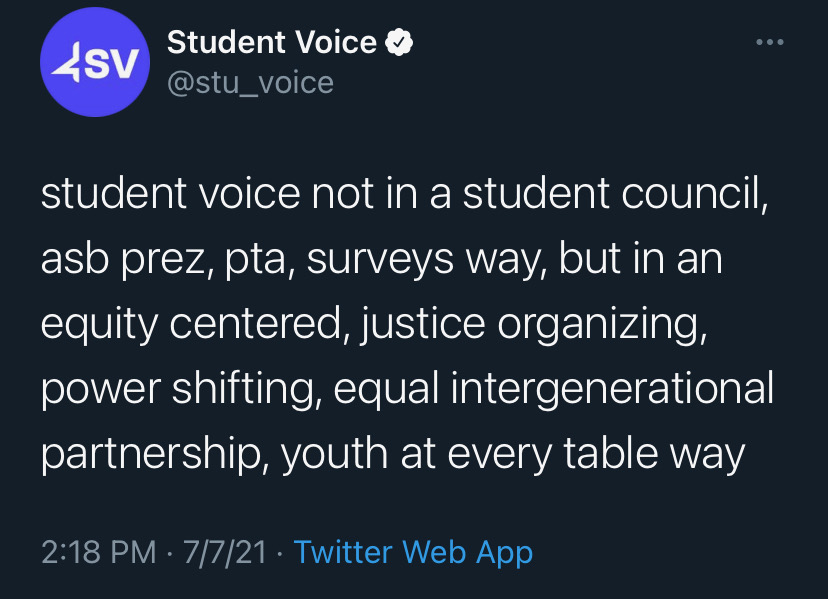

Founded in 2012, Student Voice was an entirely youth-led nonprofit that offered organizing and storytelling training programs for high school students, coached “adult-led” organizations in youth engagement strategies, and launched national education justice campaigns.

For a long time, the idea that Student Voice wouldn’t last forever represented my worst fear and my biggest failure.

Today, however, I’m proud to see Student Voice acknowledge the limitations of our solely youth-led approach and invest in the future of intergenerational leadership in the education justice movement with a six-figure donation to the Kentucky Student Voice Team. This decision embodies my ever-forming beliefs about the support structures youth leaders deserve.

With a few years of distance from Student Voice, I’ve settled into a new role as an adult ally, supporting youth-led education justice organizing. As I navigate this personal and professional transition and attempt “a practice of learning in public,” I want to share my emerging takeaways:

Youth leadership shouldn’t mean shoving students off the deep end and seeing who sinks and who swims.

While some young people can thrive with little structure, most people of all ages need scaffolding and clarity to step into leadership and access agency. If youth voice is ultimately meant to shift who has power, students need 1) political education that connects their lived experiences to the structures and systems around them and 2) leadership training in organizing and storytelling practices to create change. Without robust support—that often, but not always, requires full-time adult staff—“youth-led” efforts place students with the most access to civic infrastructure on a pedestal, while unwittingly keeping others out of the very spaces claiming to elevate their voices.

The national education justice movement needs policy demands that go beyond youth and community voice.

As the school system’s primary stakeholder, students deserve a voice in education policy, but a national movement needs an outcome that goes deeper than just getting students at the table. What are they demanding once they have a seat? At its most harmful, calling for youth and community voice without an accompanying agenda leaves students vulnerable to having their voices tokenized and co-opted by forces that are not values-aligned.

Absent of harm, a lack of coherent demands prevents students from taking full advantage of the moments when they have won decision-making power. When Student Voice finally landed our long-sought invitation to meetings with the Biden-Harris administration, we were alarmingly ill-prepared to ask for anything beyond representation.

While national education tables have identified organizing trends and priorities—like opposing school vouchers and elevating community schools, uplifting teachers unions who bargain for the common good, or fighting for police-free schools and anti-racist curriculum—the education justice movement lacks an aspirational visioning agenda such as a Green New Deal. For student leaders to win lasting policy change on a national scale, they need a symbiotic relationship with an education justice movement that’s clear about what it wants to achieve.

To win real change, we need to build authentic intergenerational power.

It’s the height of hubris for young people to believe we’ll solve generations-long injustices in our own lifetimes all by ourselves. Anchoring youth-led fights in the lineages and lessons of movement history not only provides valuable learnings, but also situates us in a tradition that can teach us to sidestep our own egos. Connecting with movement elders in our communities is an important first step.

Simultaneously, it’s a dangerous acceptance of the status quo for adults to say “the kids will save us” and abandon the fight. Every generation has a stake in building a more just future, and young people don’t benefit from adults placing unwavering trust in our leadership with no accompanying support.

Adults can be partners in operating nonprofits that affirm young people’s humanity and exercise legal and financial responsibility.

Young people operating nonprofits find ourselves facing a false choice between a cold corporate language of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) or hours spent in conversation about structure and hierarchy that resemble the worst caricatures of Occupy Wall Street. Under a tax code that resists shared leadership and is wholly unconcerned with dignifying our peers beyond their performance at work, those of us hoping to lead organizations in a more human way lack models to build from. While creating mechanisms from scratch to manage IRS reporting, budgets and job descriptions, youth leaders quickly feel overwhelmed and guilty for replicating capitalism’s worst hits. Adults who already have practice navigating and challenging the legal and financial reality of our current world can help youth leaders create new operational systems that more closely resemble the world we seek to build.

Finally, while the revolution may indeed not be funded, movements do need money.

How nonprofit leaders and philanthropic organizations navigate this tension is key. Funding incentive structures can easily warp the ability of youth-led organizations to organically represent student agendas. Faced with the pressure to keep the lights on, even the most disciplined nonprofit leaders struggle to resist the latest funding fad. Funders need to acknowledge this power dynamic and cede control to on-the-ground leaders through multi-year, general operating grants. While the instinct for youth leaders new to nonprofit fundraising is usually to criticize the source of funding, often the more revealing question is, “What strings are attached to these dollars?”

Looking back, I’m proud of the campaigns Student Voice led around college access, school reopenings, school board elections, government representation and student speech rights. I’m proud of the leaders we developed, the ideas we tested and our bravery to fail forward. Above all, I’m proud to have held space for young people while the world burned around us.

As we say goodbye to Student Voice, I know that student voices aren’t going anywhere. Across the country, high school students are organizing to win in their schools and communities. The United States Students Association is on the precipice of a historic relaunch on college campuses. Student storytellers are filling the void left by cuts to local newsrooms. Through it all, I’m more grateful than ever to be a lifelong learner in intergenerational movements for change.